The subject is brides.

From the start, “Preserving a Family Collection” has been a supplemental blog to the main attraction, June and Art. The work of preservation is never an end in itself. Works are preserved in order to help us tell stories, to remember our past, and to continue to appreciate the work of our ancestors.

The story of June and Art culminates today with a bride, a groom, and a wedding. And these blogs end here today on September 1, 2011, the 60th anniversary of the marriage of June and Art.

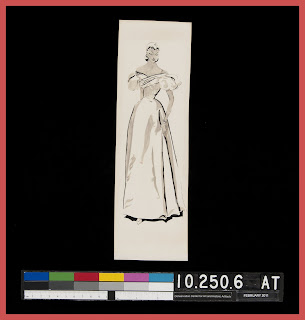

My mother (June) loved brides and weddings. She drew several fashion illustrations of brides while studying at Traphagen School of Fashion from 1948 to 1950. Several years ago, I had the watercolor image of two brides cleaned, matted, and framed at the Conservation Center

Thank you to Rachel Wetzel, Conservator at the Conservation Center

And thank you to the followers and readers of this blog, “Preserving a Family Collection.” Take care of your stories. And best wishes for your efforts to preserve your family collections.

And thank you to the followers and readers of this blog, “Preserving a Family Collection.” Take care of your stories. And best wishes for your efforts to preserve your family collections.