It’s been several decades since projectors were a normal part of our family life. Back in the 1960s, I remember times when we would set up a projector and a roll-up tripod screen in my grandparents’ living room. My grandfather would show us home movies and trick special effects scenes that he’d shoot with the family, as well as some professional reels that he must have bought somewhere (I vividly remember one that showed a lion or tiger being caught in a pit and then lunging toward the camera to escape!).

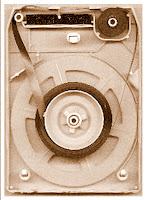

Within the family, we had 8mm, Super8, Dual 8, and 16mm projectors. Even under the best conditions, these machines would occasionally malfunction. The film would jam, or the splices would break, or the pickup reel would neglect to turn and film would spool onto the floor.

Now let’s say you find some old film in the basement, conveniently stored away with the dusty old projector. Is it time to blow off the dust, plug in the projector, and let the good times unreel?

I asked Snowden Becker, co-founder of the annual international

Home Movie Day event and the nonprofit

Center for Home Movies, about the risks of loading an old film onto an old projector.

She recommended extreme caution:

“It’s quite common for people to find a projector and other equipment in the attic along with that box of films. My general recommendation, though, is NOT to just throw those reels on that projector. Although film was made to be projected, and is comparatively durable, older film is still subject to shrinkage, torn sprocket holes, and brittleness that makes running it through a projector without careful inspection and preparation extremely risky.

“Home movies are typically shot on reversal stock; that is, the film exposed in the camera is processed to become the positive element that you run through the projector. This means that the reel you hold in your hands is a unique original, with no associated negative or copies. For this reason, it’s especially precious.

“Home movie collections often include film in multiple formats – a mix of 8mm and Super8 is quite common, for instance, and the differences are not immediately evident to someone who doesn't handle film often. Even if you have a Dual 8 projector, which can run either of the 8mm formats, you must be very careful to configure the projector properly before you run a reel through it. Improperly projected film can be quite efficiently destroyed. And even if you know how to use the projector you find in your attic (I know there are lots of A/V Club alumni out there who can still thread up an old Bell & Howell Filmosound!), chances are that if it’s been sitting unused for a long time it’s in need of new belts, bulbs, fuses, or just a good cleaning and lubrication before it is safe to use with even the most pristine film.

“At Home Movie Day events, the first step is careful inspection and preparation of the films brought in by participants, including cleaning, identification and replacement of unstable splices, checking for shrinkage or other dimensional instability, and application of fresh leader at the beginning and end of the reels. Films in projectable condition are then shown on clean, well-maintained equipment by people who know how to operate them. If you want to see your family films under the safest possible conditions, the best thing to do is to find a

Home Movie Day event in your area and take advantage of that once-a-year opportunity to get free expert advice and helpful information. You can also share those images with members of your local community, who can help you identify people, places, and activities in your movies that might be a mystery to you!”

© 2011 Lee Price